Brother review by The Grim Ringler

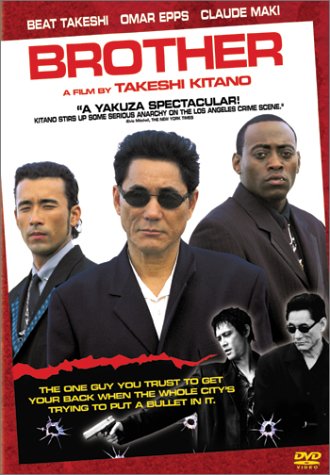

Few people in America know who the hell ‘Beat’ Takeshi Kitano is, and well, why should they know? Well, it’s no wonder really as Beat Takeshi is really only known primarily to his Japanese fans and to movie nerds who follow his work over here. Heck, most American movie nerds would only know him as an actor, and not a director, because of his turn as the evil teacher in the film Battle Royale. But what his fans have come to love about him is not his turns before the camera but those behind, to which Brother is a prime example.

Brother is the story of Aniki, a lieutenant for a Yakuza crime syndicate in Japan. When the head of the family is gunned down though the family reluctantly joins with another clan and the rest of his own clan abandons Aniki and he is summarily banished to America to live in exile. Aniki moves to Los Angeles and seeks out his half-brother whom he had shipped to America as a child, hoping to find at least some connection to family again in this strange country. What he finds is that his brother, several years younger, is a low-level hood and that this is their life. Seeing an opportunity to start anew, to create something from nothing, Aniki then organizes his brother and his friends and slowly they start wiping out any and all competition until they stand at the top of the heap with the Italians as the main force of power in the city. And slowly they have become a family, an American Yakuza gang that has power, money, and has grown cocky with its success. But as the others revel in their success Aniki pulls away, always distant, always silent, always watching. It’s as if he knows that what they have will not last, but that it is all that he, or any of them, can ever know. In his silence is doom. And his silence grows as he loses his last true link to his old life, his friend that had followed him from Tokyo to America to be by his brother’s side. A man who so loved Aniki that he shot himself to prove to a rival gangster that Aniki’s clan wanted to merge with, how deeply he was loyal to his friend. But as Aniki is pulling away, within himself, the rest are plotting their takeover of the Italians so they can finally own the entire city and be the most powerful family. This though, will prove their undoing as they have finally taken on a foe they cannot overpower or overtake, and this is one war they cannot win.

In a way, Kitano’s Aniki is a ghost in the film. A malevolent spirit that dooms and damns his brother and his friends, but that lets them create the doom in their own way. Kitano, in many ways, is Japan’s Clint Eastwood in that he lets his silence speak more for him than his own lines ever do. Preferring to use his body and his empty stare to develop his characters. And the beauty of his films is that he, like M. Night Shyamalan prefer to tell their stories away from the action. For example, there is a moment in Brother where Aniki’s gang go on a foolish raid against the Italians and it’s a bloodbath and the entire scene Takeshi focuses not on the gunfight but on the face of a dead teenager that was in Aniki’s gang but opted to kill himself rather than be killed, only seeing the aftermath of the gun battle. And as frustrating as it may be to a Western audience, it’s a brilliant way to slow the film down, and to make you realize that, no, this isn’t about the guns and bullets, it’s about these people. It’s about the fact that these are boys playing at being men, and that are dying for it. Aniki and his dead friend are the only ones that realize what it really is to be a Yakuza, Aniki seeming to hate it but not know what else there is for him. Like a prisoner released into the world with no hope of a future because they no nothing but prison and crime.

Brother is definitely an acquired taste though as it’s a very slow, very dark film. This is not an American gangster movie with a lot of action and bloodshed. And frankly, at it’s heart, it isn’t as much a gangster movie as it is an examination of brotherhood and what it means to call someone brother. In the film Aniki is closest not to his own brother but to his brother’s friend Denny (played ably, if not outstandingly, by Omar Epps) and it is their brotherhood and growing friendship that is at the heart of the film. And it is not easy to watch a film where you can feel that everyone is doomed, that no one can escape, but that is the lifestyle of the Yakuza and of gangsters – there is no freedom. There is only conquest and defeat.

I initially saw Brother in the theater but recently watched a dub from an Asian bootleg a friend had gotten that as a bit more blood than the American release. All told though it’s the same film either way. The thing about the violence in Kitano’s films is that when he does it, he does it all out. but again, it’s usually just something that happens more than the showpiece of the film. As in the case of a dishonored Yakuza who must cut off a pinky to re-gain favor – you hear it, you see the aftermath, but you don’t see the finger removed.

A lot of people won’t get this, and will hate the film for what it isn’t. Heck, I just read a review damning the movie for having subtext. This is not a perfect movie, it is slow, and plodding, and at times the silence of Aniki is maddening, as is his inaction, but it is a beautifully made film and it is nice to see a gangster movie that has something deeper to say than – crime sucks. Well worth a look if you are feeling adventurous.

…c…

7 out of 10 Jackasses blog comments powered by Disqus