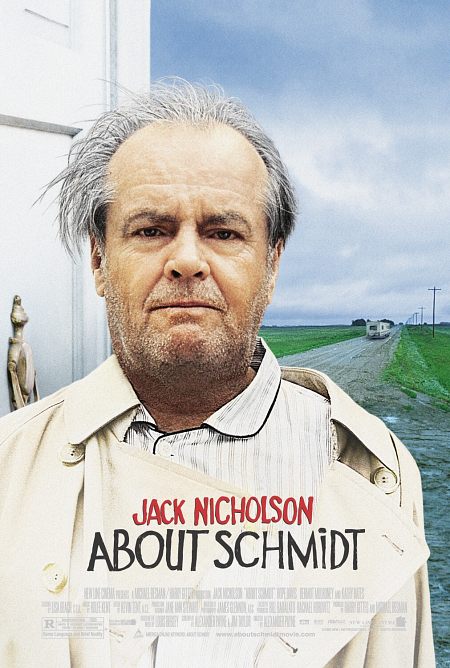

About Schmidt review by Jackass Tom

Good ole Jack

About Schmidt is about how one man breaks down when the structure he has devised in his life begins to fall apart. It is sort of a “can’t teach an old dog new tricks” film. As the audience we are immersed into his daily life both good and the bad. It starts with his alarm clock that he no longer has to set because he routinely wakes up 5 seconds before it would go off. He heads off to work an hour later and leaves (even on his last day) at 5pm on the button. Life with his doting wife has become irritatingly routine as he notices every single one of her minute (that would be My-Noot, not Min-It) idiosyncrasies to the point of systemic annoyance. The way she has her keys ready before she gets to the car, the ceramic figurines she collects, and even the way she plunges her posterior into a chair when she sits down begin to drive Schmidt mad.

Over time everything around him starts to fall apart. He retires and therefore loses his job. Schmidt struggles to fill those eight hours of the day in any sort of way. Shortly after his wife has a brain anuerism and passes away. This leaves him without cooked meals, a clean house, or even just someone around the house. As cold as it sounds (and ‘he’ makes it sound cold, not ‘me’) there seemed to be little love left between him and his wife. After the funeral, it seemed like the only remorse or depression he experienced were due to the routines she created for him, that were now dissipated. More than anything else she was the person holding him up behind the scenes, keeping him alive, and taking care of his odds and ends. Soon after, other things start breaking down around him. Laundry piles up, his hair is uncombed, meals become microwave dinners, dishes are no longer cleaned, and the refrigerator becomes a bacterial habitat. Even obstacles like his Cadillac breaking down are beyond his means (he would rather take the Winnebago to the grocery store than repair it).

After his life falls apart, he spends the rest of the movie on an odyssey attempting to adapt to a changing world, cope with his losses, reason with a life of disappointment, and learn (which is the tough part) how to understand people around him. He travels the flat Midwest in his brand new Winnebago, re-visiting his past trying to figure out what has happened over the past 60 years. He visits his place of birth (now a tire store) his old college frat house (where he is 40 years out of place) and Colorado where his daughter lives (who doesn’t want him there until the wedding or else he will get in the way). What has he accomplished? Who will remember him? Will anyone care if he is gone? What is his place in life?

One of his toughest challenges is accepting his daughter’s (Hope Davis) soon-to-be marriage to a mullet-headed, white trash dude, Randall (Dermot Mulroney). Like any loving father, he believes his daughter is marrying below her means. He argues with her a number of times, treating her like a little girl who must follow her father’s strict but fair orders. As the film progresses, he realizes that he no longer has that sort of power over her. He is becoming part of the out-dated and ignored generation of senile old men. During the wedding he delivers what is intended to be a heart-felt speech, but it is obvious he has reservations.

Randall’s mother (Kathy Bates) is a model trashy living. She puts her bare feet on the table to relax, leaves empty paint cans strewn about her lawn, and owns a waterbed. Yee haw! Even her attitude lacks any class as she yells at her ex-husband in front of guests, talks openly about her past/current sex life, and (best of all) she goes skinny-dipping with poor Warren. That’s right, you get a full (till it overflows) frontal of Kathy Bates and it’s not pretty. Klass with a ‘K’!

Some of the most comic and most open parts of the movie come in Schmidt’s letters to his African foster child, Ndugo. He comically pours out his soul like most men would in front of their favorite bartender. Schmidt is oblivious to the fact that Ndugo lives in a poor village in Africa and may not be able to “join a fraternity one day” or see this really great “highway overpass between Kansas and Nebraska” let alone live through the week. The letters to Ndugo become an outlet for his honest emotions. There is no one in the film that he sees eye to eye with: he has no true peers, no true friends, or anyone that he can open up to. Even when his wife was alive their little communication seemed as complex and open as discussing coupons from a newspaper. He writes everything he sees filtered through his eyes and poor little Ndugo gets more than just the $20 a month.

The best part about this movie (aside from the white trash intricacies) is how little Warren Schmidt actually changes as a person. How true is that? It doesn’t have the beautiful Hollywood ending where the characters change their attitudes on life to conform to what is ‘healthy’. Towards the end, he still disapproves of his daughter’s marriage and grudgingly wishes her well as he leaves for home. His home is still a mess, and he still doesn’t know what he has done with his life or whether he has made a difference (with the exception of possibly saving the life of Ndugo). But, all in all, he comes out of it, pretty much the same man he was before. The job Jack Nicholson does with this character is about as true as they come.

8 out of 10 Jackasses blog comments powered by Disqus