No Country for Old Men review by Rosie

Author’s note: A slight break from the shtick this week to follow up on a promise made in last week’s 2008 Academy Awards Diary to return and try to give this movie its proper due. Unfortunately, there is no way to really explain the richness of this movie without delving into potentially spoilerish discussion. I’ll do my best to not reveal specific plot points, but will be touching on certain aspects of perspective that you may prefer to try to discover on your own if you haven’t seen it yet. Just imagine if, before you had seen The Sixth Sense for the first time, you would have wanted to read a review that spoke openly about the ending twist in order to give M. Night Shymalan his due credit for the specific ways he constructed the story building up to it. Normally I wouldn’t want to pull back the curtain so far on a movie that so many people still haven’t seen, but after all the campaigning I did (and still stand by) for There Will Be Blood, and all the crap I’ve been giving the Coen Brothers for their win, I figure I owe it to the movie cosmos in some way to be wholly honest in giving them the credit they deserve in this, my Best Picture and Best Director concession speech. Feel free to click out of here now and return after you’ve seen the movie dry once. Also, with the time you would have spent reading it now freed up, feel free to sit there clicking back in and out of this review a couple dozen times to get my traffic up.--

No Country For Old Men

In retrospect, I guess we all should have seen this coming. It was almost two years ago now that two big, Hollywood productions both inexplicably chose the same, little west Texas town of Marfa to film in at the same time. Both productions found themselves quickly in competition (for the first of what would be many more times) for the precious space and resources available in what Daniel Day-Lewis succinctly described as “not a two crew town.” One day, the two brothers directing one of the films were forced to halt production for an entire day, when the sky above their landscape became filled with a gigantic cloud of black smoke from the nearby explosion of an oil derrick, set off by the director of the other crew. From that day on, we all should have known, No Country For Old Men and There Will Be Blood would be forever destined to compete with each other. And just like the small town of Marfa, Texas turned out to be, the Academy Awards spotlight weren’t big enough fer the two of ‘em.

And so it came to be that with four brief words on behalf of the Academy last month: “No Country for Old Men”, Martin Scorsese struck the final blow in one of the most hotly contested film rivalries in recent memory. So how do those of us in the There Will Be Blood/Paul Thomas Anderson booster club make sense of it all? Well, actually, pretty easily.

No Country for Old Men centers largely on the relentless fixation of a sociopathic killer named Anton Chigurh (pronounced ‘shi – gurr’) (Javier Bardem) as he hunts a Texas welder named Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) across a number of towns and borders to recover a bag of Chigurh’s money that Moss stumbled upon and took while out hunting one day. Along the way, Chigurh remains fixated on moving in a straight line towards Moss at all times, killing or pushing aside effortlessly anyone who steps in his path, practically staring straight through them to keep his gaze fixed over some distant horizon and onto Moss and his money all the while. Tommy Lee Jones plays Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, a grizzled and quickly becoming exhausted Texas sheriff trying to get to Moss before Chigurh finds him, and trying harder to convince himself he still cares enough about his job that it matters to him anymore whether he actually does so or not.

The result is a pretty good story, pretty well told. A movie I might, at first glance, describe just as “solid”, in every way. But Best Picture? I can’t say that I would have believed that at the time I was watching it. So the question then became, “Why?” And it was in an effort to make sense of this question that I finally began to see what I had at first missed in the way this film was crafted at the skillful hands of the Coen brothers.

*************Warning: Contains Spoilerish Analysis*************

Given the amount of time the film spends following him on his quest, as well as the overwhelming attention focused on him and his He-Man haircut in the advertising and marketing of this film, you could be forgiven for thinking (as I certainly did) that this movie is about Anton Chigurh. Or, even, about Llewelyn Moss. But the real story here is actually about neither of them, the story here is all about Sheriff Ed Tom Bell. It doesn’t make sense to think so, at first, but it’s the only thing that makes sense once you realize it. It is also the slight shift in perspective needed to realize why all of the accolades showered over this otherwise gritty, little chase movie might make sense, as well.

The simplicity of this bit of deception is probably what sealed the deal for the Coen brothers as Best Director winners this year. When you consider that Jones as Bell was both a main character and the film’s narrator, not to mention the fact that Bardem’s Oscar for Chigurh was for Best Supporting Actor, it would seem pretty obvious who the story is about. But Joel and Ethan Coen know that the secret of misdirection is to just capture the eyes and the mind will follow. They use this simple ploy with the practiced ease of a master magician to trick the audience into forgetting reason and accepting what they see in front of them. With the kind of confident arrogance that a younger M. Night Shymalan once brought to The Sixth Sense, the Coen brothers similarly lay out a story right before us that remains hidden only by our own failure to see it. Our faith in the infallibility of our own senses turns out to be the only source of any confusion necessary for them to keep us on the hook. We see Anton Chigurh more. We see Llewelyn Moss more. We hear from them both more often than anyone. And we assume, because of this, that this movie is about them. Knowing this, the Coen brothers don’t need to make any effort to hide the fact that this story is always about Bell. They know we won’t even notice until they’re ready to point it out.

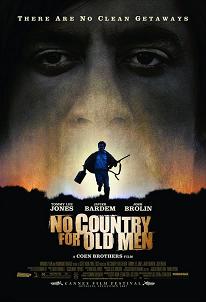

Perhaps nowhere is the essence of this stunningly simple sleight of hand more perfectly encapsulated than on the quickly becoming iconic poster for this movie. Who do you see on it? Who do you not see on it? What do you see on it that your mind decides not to factor in because of who you see? Does your mind let you consider the fact that Tommy Lee Jones has top billing? Or even that the title is No Country for Old Men? A title that our reason would tell us makes no sense at all for the story we infer from the picture, if we hadn’t become so adept at repressing our own ability to reason when it comes to processing information given to us on screens. And, trust me, I include myself as guilty of this as anyone.

Once we get over this, though, the floodgates open on this movie and all but necessitate a second viewing. Through the eyes of Bell, the characters all become transformed from literal people into symbolic entities and the inevitability of how all of their stories must end becomes a realization that both Bell and the audience arrive at together. The most apparent commentary embodied by the characters is on the increasing desensitization to (or acceptance of) images and acts of violence with each new generation. This is one observation where the Coen brothers flex their directorial nuance brilliantly, and one of the reasons I can understand the choice to give them the Best Director prize this year (though I still maintain it could have been a coin-flip between them and Paul Thomas Anderson). For example (and to avoid continuing to sound too ethereal about all this great “symbolism” stuff), consider the way the violence of Chigurh progressed in the eyes of the audience. The first time we see him kill, it is raw, jarring, and on camera from beginning to end – as though we can’t look away – including a moment taken to linger and look over the aftermath. The second time we watch and it is just as raw, but this time it’s quicker, a little less painful, and we’re already moving on to the next thing as soon as it’s done. Kind of feels like just ripping a band-aid off quick this time. As the film continues to unfold, Chigurgh’s violence becomes less and less explicit to us, until eventually we don’t even see him kill his victims anymore and just assume, unfazed by the idea, that he did.

Though the commentary on violence seems most explicit, the story of Chigurh and Moss can be seen to embody any number of symbolic themes. Chigurh’s shoeless relentlessness is a clear visual reference to the creeping death steadily gaining on all of us, no matter how far or fast we try to run, but the story of the two of them can be theoretically seen as a cautionary tale relating to just about any human struggle involving the inevitable consequences of short-sighted choices. From fostering addictions to environmental abuse to financial irresponsibility – their story can be seen as an allegory that applies to just about any situation that the false invincibility of youth can trick men into pursuing with the belief that somehow they’ll find a way to avoid paying the piper for in the end. Bell’s own perspective can remain unchanged in any of these versions, the wizened older generation who finally understand what it means that “the world ends not with a bang, but with a whimper,” and who are torn now between wanting to help the next generation before it’s too late for them, and the nagging awareness that nothing they say could really make anyone understand. That the piper always gets paid in the end, is a lesson you can only learn the hard way. (There’s a great quote by Bell reflecting this idea that was completely lost on me the first time I watched, and completely jumped out the second time. I won’t give it away, but watch for it when Bell and another cop named Wendell are looking for Moss at his trailer just after he’s skipped town.)

The bottom line is that this is just a rich, complex, well-crafted, excellent movie. Personally, and for the record, my opinion that There Will Be Blood should have (or at least, justifiably, could have) won for Best Picture and Best Director remains unchanged in spite of all that I’ve written here. I only regret not having done a better job explaining the case why in my haste to enshrine it in rhyme. (At the time I just figured the reasons would be self-evident to anyone who’d seen it and, if not, there would be ten-thousand other reviewers breaking it down and gushing about why it should win.) Maybe someday I’ll revisit the topic to do so, but for now it’s a moot point. No Country For Old Men was named the Best Picture of 2007, and I totally understand why.

10 out of 10 Jackasses blog comments powered by Disqus

Search

No Country for Old Men

IMDB Link: No Country for Old Men

DVD Relase Date: 2008-03-11

DVD Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1